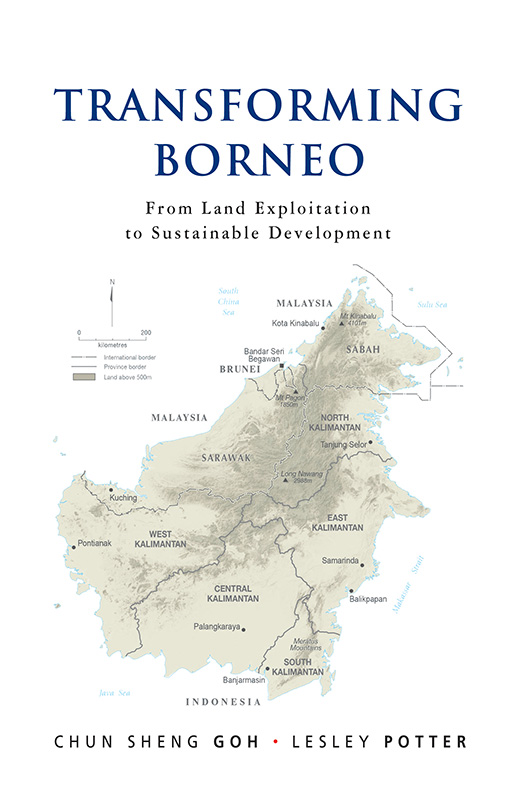

Chun Sheng Goh and Lesley Potter, Transforming Borneo: From Land Exploitation to Sustainable Development (Singapore: ISEAS, 2023)

Book Review by Dr Matthew Woolgar, Lecturer in Twentieth-Century International History, University of Leeds

This volume considers the challenges of transitioning Borneo from a growth model that has involved serious environmental degradation to a future trajectory that improves its population’s welfare in a way that is sustainable from social, economic and environmental perspectives.

The book starts by providing an overview of Borneo’s economic and environmental development from 1970 to 2020, tracing key developments including massive timber extraction, the expansion of coal mining, a huge attempted peatland reclamation project, and the rapid rise of palm oil production. Since around 2010 there has been a growing consciousness of the importance of a more sustainable approach to development, and deforestation has slowed, but it is still highly uncertain whether environmental destruction can be halted, let alone reversed.

The scale of the transformation outlined in the book’s introduction is epic. During the period 1970 to 2020, likely more than 200,000 km2 of old growth forests were destroyed, representing around a quarter of the total surface area of Borneo. Meanwhile the island came to be the predominant source of coal for Indonesia, which has become the world’s largest coal exporter. Borneo is also now a globally significant source of palm oil exports.

The environmental and social impacts of this transformation have been stark. In addition to biodiversity loss, and growing greenhouse gas emissions, the island has suffered from severe fires (exacerbated by degradation of peatland) that have been a major contributor to recurrent international ‘haze’ air pollution crises in Southeast Asia. One estimate suggests the carbon emissions from a single month of Indonesia’s forest fires in 2015 released as much carbon as Japan’s entire emissions for that year. Moreover, the authors highlight that the economic benefits of growth have been ‘mostly concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites, creating huge wealth gaps’.

The heart of the book is a consideration of various strategies to ‘improve livelihoods’ without further damaging the environment (and if possible repairing damage that has already occurred). It divides these strategies into two broad baskets.

One basket is ‘bio-economy’ or ‘productivity-oriented’ strategies, such as increasing the productivity of cash crop production, developing ‘downstream’ production (such as the industrial processing of raw materials), and making use of land that has previously been degraded or abandoned.

The other basket is ‘eco-economy’ or ‘conservation-oriented strategies’. These include improved planning and governance, environmental restoration projects, developing mechanisms for financially quantifying environmental impacts, building a green service sector (for example via eco-tourism) and promoting ‘traditional land use systems’.

The book carefully considers each of these strategies in turn, considering both their potential and limitations. The overall picture that results is a complex one, as ‘the interconnected nature of economic productivity and conservation means that no single strategy is a perfect solution’. There is no silver bullet to achieving sustainable development in Borneo. Rather, the authors conclude that ‘a carefully crafted combination of strategies’ offers the best prospect of enabling a shift toward a more sustainable development model.

While the analysis of each of the strategies identified in the book is valuable, discussions of two aspects may be of particular interest to international audiences. One is regarding systems for certifying cash crops as sustainable, which has sometimes been linked to market access in contexts such as the European Union. Another is regarding international schemes providing financial compensation for developing countries implementing environmentally friendly policies. An example is the REDD+ programme (REDD standing for ‘reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries’) which has been in operation in parts of Borneo. The book is open to these approaches forming part of the solution. However, it also highlights various complexities and limitations, for example pointing to the challenges posed by the proliferation of different certification approaches and the difficulties of quantifying economically the value of non-carbon-related environmental impacts.

This book provides a valuable overview of Borneo’s development and challenges, complementing various existing studies on specific economic sectors or localities. The book is helpfully broken up into subsections and is generally written remarkably clearly, given the breadth and complexity of the subject matter. The book covers developments in both Indonesian and Malaysian Borneo, and has much to offer potential readers interested in development and environmental issues in Southeast Asia or globally. Academics, journalists, activists and policymakers can all benefit from engaging with this book.

In the conclusion the authors raise the ‘insidious’ risk of climate change to Borneo. Based on projections from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, the authors highlight that without significant progress on climate change, Borneo faces the prospect of frequent instances of dangerous temperature levels, increased risks of fire and flood, as well as major disruption to crop production. This reinforces the importance of more sustainable approaches to development and highlights the interconnections between Borneo’s future and that of the wider world. It also further underlines the urgency of the contribution of this important book.

Cover image: Coal Mining Site. Photo by Parolan Harahap on Flickr.